Cathedral

The Cathedral, the beacon in the alleyways of the old town, Bari Vecchia

The most recent of Apulia’s Romanesque cathedrals, this monument recounts the four historical phases of its existence; decorations and sculptural details celebrate The Victory of Christ – Light – over Darkness, exalting the afflatus of mediaeval man in uniting spirituality and art.

Historical Notes

The origins of the Cathedral of Bari are rooted in the ancient early Christian church (5th and 6th centuries AD) that came to light in the 1960s thanks to some successful excavations; its appearance remained unchanged until the mid-11th century, when the Byzantine reconquest coincided with the reorganisation of religious power and the construction of a new sacred building. According to tradition, in those same years, the relics of St Sabinus, bishop of Canosa, were transferred to Bari: the new temple was dedicated to him, and the saint also became the patron of the city.

The year 1156 was a fateful one for Bari; the Norman William the Bad or Wicked ordered its destruction following repeated popular uprisings: not even the Cathedral was spared. A few decades later, the people of Bari were allowed to return to the city, and reconstruction of the sacred building began under Bishop Rainaldo: on 4 October 1292, the present Cathedral was officially consecrated.

The rose window of the façade seen from the central nave

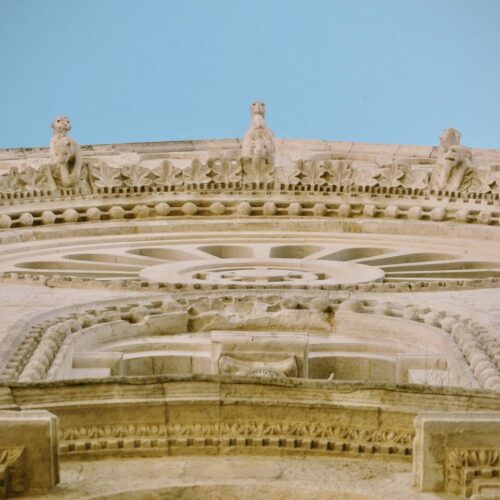

Detail of the main façade

Exterior

A shining example of the Apulian Romanesque style, the main façade in white limestone is adorned with small arches and pilasters; the element that really draws attention is the rose window, consisting of eighteen spokes (to resemble petals) and a semi-circular frame adorned with corbels and striking grotesque figures of animals. On 21 June – the day of the summer solstice – there is a special phenomenon: the sun’s rays pour in through the 18 segments of the rose window, perfectly matching the petals of the rose that decorates the floor of the nave.

The south façade also features a rose window composed of 21 small columns ending in plant decorations and grotesque heads; the façade has a tiered or gabled roof, with a series of blind arches, ending in corbels decorated with bestiaries.

A tall bell tower made of white limestone makes the exterior even more impressive; there are mullioned, three, and four-light windows, all the way up to the pyramidal spire.

The interior

The three-aisled nave in the interior has two rows of slender columns, and the very fine marble decoration is attributed to the great sculptors of the time – Alfano da Termoli, Anseramo da Trani, and Peregrino da Salerno. The wall frescoes, of which valuable fragments survive in the minor apses and Crypt were also very elaborate.

High above the nave is the transept with the 13th-century ciborium or canopy by Alfano da Termoli, in the centre: the three access steps decorated with plant motifs, animal designs and a hexameter celebrating man are a clear reminder of the three kingdoms.

The pulpit that stands out along the right aisle has been reassembled from original 11th and 12th-century fragments; the two Romanesque lions placed on either side of the staircase that ascends to the chancel are quite beautiful.

In the centre of the main apse, the apsidal window is a masterpiece of mediaeval sculpture that illuminates the altar: Christ, the Light, defeats the Darkness. The interior cornices are finely crafted, as well as the protruding exterior cornice, recalling the similar window in the basilica of San Nicola and the Cathedral of Trani.

The 13th century ciborium by Alfano da Termoli

The cross vault of the Crypt

The Crypt

Below the transept, access to the Crypt is provided by a double flight of stairs that retains the Baroque appearance given to the cathedral in the 18th century. The four-aisled nave supported by three rows of columns and covered by a rib vaulted ceiling, is of a shining delicate green colour enhanced by details in pure gold.

The relics of St Sabinus are worshipped below the high altar, inlaid with polychrome marble; in front is the altar of the Virgin Hodegetria. It illustrates the arrival in Bari of the icon dedicated to the Madonna. In ancient times, the church was dedicated to this Madonna, and during World War II Archbishop Mimmi had the icon moved here so that it would protect the city.

The Virgin Hodegetria

The icon preserved today in the high altar of the Cathedral’s Crypt dates back to 1500 and is the work of Francesco Palvisino. Venerated first in Jerusalem and then in Constantinople in a basilica along the Via Odilonica – the “way of righteousness” – it took the name of Santa Maria Odegitria [the Virgin Hodegetria], she who indicates the path to righteousness.

Today, the Virgin, who with one hand shows the faithful the right path and with the other holds her standing Son in her lap, is the patron saint of the Diocese of Bari and is celebrated on the first Tuesday in March each year.

The archaeological area

The Crypt leads to the Succorpo, the room that recounts the cathedral’s earliest history.

Five metres below the church, a museum tour brings the four main historical phases back to life: the Roman era, the early Christian era, the mediaeval era, and the modern era. Roman ruins datable to the 1st-4th centuries AD stand alongside features from the ancient Byzantine church, built right on top of the remains of the Roman building from the 5th century AD onward; mosaics and frescoes recount the splendours of a past brought back to light thanks to successful excavation work.

The Mosaic of Timoteo, named after its patron, is the largest early Christian floor piece to come down to us; polychrome tesserae in different materials (marble, limestone, brick) give life to aquatic animals, plant and floral motifs and complex geometric shapes.

In 1034, Bishop Byzantius had the early Christian basilica torn down to create a larger church, the first mediaeval cathedral, completed in 1064; in 1156 this building, as well as the entire city, was destroyed: only traces of the Succorpo remain here.

The Mosaic of Timothy

ArtEcclesiae is carried out by Artwork with the Archdiocese of Bari-Bitonto

ARTECCLESIÆ BARI-BITONTO

Piazza Odegitria

70122 Bari

Tel. 329-2697374

Email: info@artecclesiae.it